My father is a 6-4 Black man with a slight Southern twang. It rings out in a type of singsongy acoustic dance when he surprises me with a phone call or greets me after not seeing me for a few months.

It's the type of voice I'm sure George Floyd's five children are aching to hear right now. Their father, a native of Fayetteville, North Carolina, is now immortalized as an unintended martyr in the continued fight against police brutality in America. He is no longer here to hold them, scoop them up in safe arms, and nurture them. And that absence is a debt that can't be repaid.

Even as the guilty verdict of Derek Chauvin hovers across the country in a hazy cloud of "justice," the genocide of Black folks spanning lifetimes will be this generation's ghost, and a wispy fog of uncertainty blurs the steps ahead toward progress.

Will the jury's decision in this case protect and shield Black folks living now and ones yet to be born? Despite my Christian background, I'm grasping for faith.

REUTERS/Adrees Latif TPX

I live every day with the knowledge that my story could become George Floyd's family's story at any time. It gnaws away at my spirit in even the most banal of moments.

While some parts of America sip their green juice, get enraged over the weather, and complain about snarky work emails, there is another America that lives in a reality where every return home is a celebration.

I remember waiting for my own father to come home.

He inherited that comforting country vocal tone from his grandparents, who moved to Ohio from Palmetto, Georgia, in the harried rush of the Great Migration.

I learned this while visiting the African American Museum of History during a family vacation to Washington, DC, a few years ago. My dad shared this defining piece of family history with me as we paused in reverence at Emmett Till's casket on the second floor of the "Defending Freedom, Defining Freedom" exhibit.

Emmett Till was visiting family in Mississippi when he was murdered in 1955. Originally from Chicago, the 14-year-old was brutally murdered by a racist mob after being accused of whistling at a white woman.

My grandparents escaped that chokehold of hatred inflaming the South a few decades before Till's young life was snatched from him. But I saw, for just a moment, in the haunting remnants of Till's casket, what life would've been like for my bloodline had my ancestors not run.

But northern flight, of course, would not stop Black wings from being clipped.

We watched another Black man lynched in the blinding light of day as a virus ravaged the world in the early months of 2020. We were reminded, once again, that America's violent, racist history is not a museum artifact. It is present, choking, and looming.

The compounding trauma of being disproportionately afflicted by the carnage of COVID-19, and simultaneously crushed under a policing system created to capture us rather than protect us, will forever live as a blight on Black American consciousness.

What did my foremothers and forefathers flee from if, just decades later, a policeman could kneel on George Floyd's neck in the light of a Minnesota afternoon until breath was squeezed from his lungs, and yet a country had to burn in fury for days for an arrest to be made?

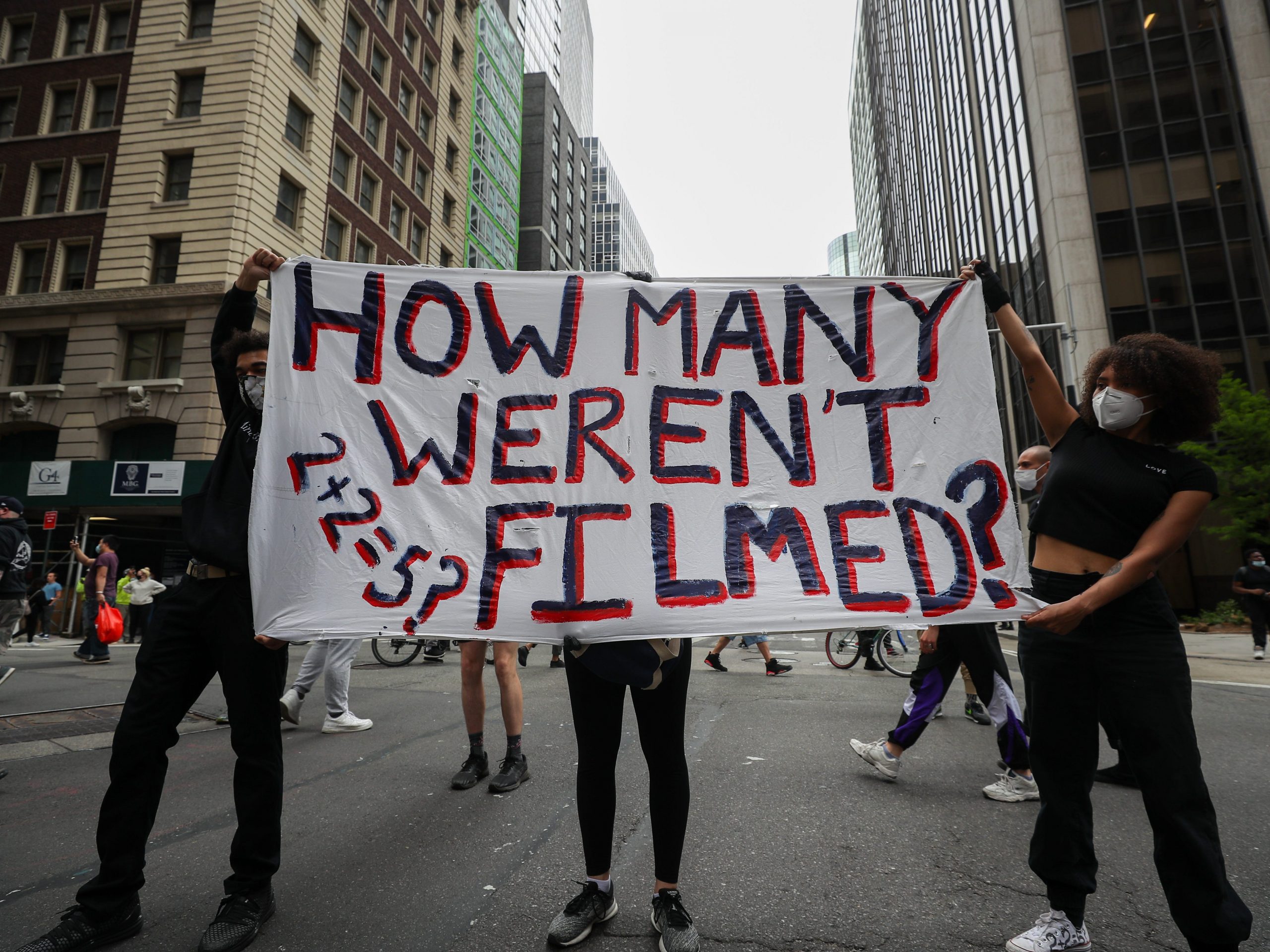

Tayfun Coskun/Anadolu Agency via Getty Images

What did their sacrifices mean if, just as that guilty verdict was being read, a Black girl was killed by police in Columbus, Ohio, hours from where I was born? Her name, Ma'Khia Bryant - another soul added to an infinite list of names that deserve to be known more for their lives than for their death.

Some Americans are sheltered from the effects of this pain. When they scroll through those obituary photos and watch viral videos detailing the last seconds of a person's life, there's inherent disassociation. The victims don't look like anyone they love.

But when I see them, I see me. My face, my features, my family. This is us.

Breonna Taylor was killed by police in Louisville, Kentucky, the city that raised my brother-in-law, the daddy of my two young nieces. Sandra Bland was just a few years older than me when she was found hanging in her jail cell after an arrest for a minor traffic violation. George Floyd looks like and represents every Black man I've ever loved and sons I have yet to give birth to.

And yet their futures remain entombed in a casket of my doubts and fears over whether this country, this world, will finally see Black people - who are my lovers, my friends, my teachers, my protectors, and, in the case of George Floyd, men like my daddy - as full and realized humans who just want to come home.

My only modicum of hope rests on the idea that cops such as Chauvin would be so fearful of the consequences of their decisions that they would think twice about their actions. I saw a glimpse of that fear - and shock - yesterday, as Chauvin's eyes, the only part of his face visible behind a surgical mask, darted around the courtroom. How could this happen to me? they seemed to be saying.

Brandon Bell/Getty Images

I am not naive enough to believe their reform would come from some enlightened recognition of Black folks as equally human and deserving of joy and freedom and more days, but rather from their own interest in self-preservation, having witnessed one of their fellow boys in blue face years in prison for spilled blood.

Even with this apparition of victory, I wrestle with the notion that I will never have peace. The only justice here is another moment for George to open his eyes and greet the sun with optimism for the coming day. The only justice is for men who look and live like George Floyd to continue to come home.